The Chicago Defender was perhaps unduly ebullient in praising Careless Love, claiming the show was “becoming as popular in Harlem as Amos ‘n’ Andy.” The Baltimore Afro-American also referenced Careless Love in relation to Amos ‘n’ Andy, declaring that NBC deserved recognition for putting the program on the air when so much radio content “simply burlesque[d]” blacks. Unfortunately for Moss, Careless Love was apparently not as popular nationwide as in Harlem. It was frequently moved around the broadcast schedule, playing on different days of the week at various times. Broadcast logs even indicate the program’s length varied between fifteen and thirty minutes. Further, as of May 29, 1931 the series was switched from WEAF to WJZ (also out of New York), which was a part of NBC’s Blue network. While any African-American project of this sort would have struggled to find a comfortable audience in that era, the constant broadcast shuffling could only have damaged efforts to solidify that audience.

To the program’s credit, when NBC Blue attempted to cancel Careless Love in March 1932, audience reaction was such that broadcasts were resumed for another two months. Ultimately, its following was not enough to save the program and Careless Love left the air on May 15, 1932, one-and-a-half years after it debuted.

An eighteen-month network run for a writer new to radio – even in this early era – should be considered a success. Just as admirable as the length of its broadcast run was the geographical diversity of stations airing Careless Love. Via its slot on the NBC schedule, the series reached listeners coast-to-coast, from Seattle to San Francisco and from Houston to Boston. In addition to these large urban centers with more significant African-American populations, the series was picked up in much smaller and whiter markets such as Council Bluffs, IA, Portland, ME, and Covington, KY.

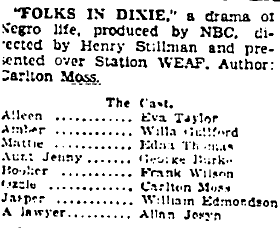

Aiding Moss in presenting these stories of African-American life every week was a company of all-black actors and actresses, many of whom had notable theater credentials. Among them were Georgia Burke, Edna Thomas, singer Eva Taylor, Frank Wilson (who featured in the original stage run of “Porgy and Bess”), Wayland Rudd, Richey Huey, Ernest Whitman, Inez Clough, Georgette Harvey, and Clarence Williams. Several of these same performers would later be cast in Moss’ subsequent radio efforts. The Southernaires, a black gospel quartet formed in New York City in December 1930, would eventually provide incidental music for Careless Love. The Southernaires were an all-black quartet comprised of William Edmonds, Jay Toney, Lowell Peters, and Homer Smith, who provided music for much of Moss’ other radio work as well. Of this group only the Southernaires could truly be considered to have become radio stars in any sense of the term, remaining on radio for two decades with their own Sunday morning show.

Moss’ sophomore effort for NBC was entitled Folks From Dixie and it debuted May 7, 1933, again on WEAF. The show replaced Moonshine and Honeysuckle, a “dramatic series of the Kentucky mountains” which had run for nearly two years. At least one critic who was initially skeptical of the programming change said “it’ll have a tough job” replacing Moonshine and Honeysuckle. He later admitted after hearing the premier of Folks From Dixie that the show was “a worthy successor to the Moonshine and Honeysuckle skit.”

Roi Ottley of the New York Amsterdam News summarized the premise of the series on one of his columns, providing more insight to the story lines of this program than of any of Moss’ other works. Set in Abbeville, GA, then in Oklahoma, stories revolved around Aunt Jenny Jackson (Georgia Burke) who inherits $50,000 from a deceased relative. Episodes revolved around Aunt Jenny’s management of the fortune, balancing her wishes with the needs of her nephew, Ozzie (Moss), and Ozzie’s beau, Amber. The wealthy villain, Jasper, provided further anguish for Jenny. Of Moss’ radio efforts detailed here, Folks From Dixie appears to be a bit of an outlier with its more humorous content.

This series did not catch the public’s imagination. Folks From Dixie ran weekly beginning May 7, 1933, only until August 6, 1933, a mere fourteen weeks. An early Sunday afternoon time slot (1:30 – 2:00) likely did not help. Interestingly, despite a significantly shorter run, it appears that Folks From Dixie achieved wider network distribution than the longer running Careless Love. Records indicate it aired on at least 50 stations, four to five times as many as Careless Love at points in its run. Similarly, the stations were even more diverse, encompassing the continental U.S.; Seattle to San Diego, New Orleans to Miami, Detroit to Fargo, ND, and all points in between. Significantly, it aired outside the U.S. on at least two stations, CFCF in Montreal and CKGW in Toronto.

A rare interview concerning this series provides modern scholars with a glimpse of the politics with which Moss dealt during his radio career. In response to a letter-writer’s request that Moss create a serious series in the nature of the Jewish serial The Goldbergs, Moss indicated he was very interested in such a program. However, NBC at the time wanted a comedy series, thus he was compelled to give Folks from Dixie a comic theme. While Moss does not complain outright in the short response, it is clear that the show’s humorous tone was not his preference. Ottley was less than impressed with the results. Couldn’t he have been “persuaded to write something more adult?” Ottley wondered. Perhaps this lack of enthusiasm by the writer and lack of support by the critics led to the program’s short duration.